In 2010, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake devastated Haiti. Artists for Peace and Justice was already on the ground, working there with the most effective local community leaders. Together they have since created two vital new institutions for Haiti’s youth: the nation’s largest high school, The Academy for Peace and Justice, and a college for film, music, and audio engineering, Artists Institute.

Students on the Academy for Peace and Justice campus watch an early morning soccer match before class. Tabarre, Port-au-Prince.

Photo by Giles Clarke / Getty Images

I first traveled to Haiti in 1993. I was twenty years old and setting out on my first documentary film project. I’d recently been introduced to the legendary black American choreographer, dancer, and Civil Rights activist Katherine Dunham, and wanted to make a film about her life. She gave me a copy of her book, Island Possessed, and said, “If you want to tell my story, you need to start in Haiti.” Three days later I was on a plane to Port-au-Prince.

That first day stepping out onto Haitian soil has remained indelible in my mind. The heavy wall of Caribbean heat and blinding sun, the rich pungent smell of food cooking on open charcoal and garbage burning, and the immediate heightened sense of humanity totally awakened me. It was a visual feast. People were everywhere. Merchants and artisans lined the roadsides making, repairing, and selling things. Students and commuters crammed into colorful tap taps (local shared transportation) that crawled across the bustling but broken roads of the city. Strong men shouldered massive loads on giant wooden carts the size of small pickup trucks. Women and children balanced wicker baskets of vegetables and buckets of water on their heads. Even the odd purse or bag was placed up there, on the head as if it was a shelf, leaving the hands free to swim through the mass of people before them. And just beyond the street’s edge were modest one- to two-room homes, most of which had a boutique of some kind in front. Windows and doors – all left wide open, life was lived in public view at all times.

In those days, blan (whites or foreigners in Creole) were a novelty. As much as I stared at the Haitians, they turned to look at me. I was a total oddity to everyone; a white boy, with straight long blond hair wearing yellow sunglasses, a black leather jacket, and green Doc Martens. Our looks were intense unbreakable gazes filled with humor and flirtation.

Somewhere along the ride across Port-au-Prince to the Hotel Oloffson, my eyes settled on something that has forever marked me. There, in the midst of it all, was a young woman squatting in a ditch on the side of the road washing her baby boy. Her eyes lifted to meet mine and I looked away out of respect. But she didn’t, she raised her chin in pride, looked down at her baby with love, smiled, and kept washing him. I’ve never been the same man since. In an instant she taught me about the dignity of the Haitian people, about the complex condition of poverty, and how utterly unjust the lottery is of birth on earth.

Since that first trip twenty-four years ago, I’ve had the great privilege to collaborate with a remarkable group of local and international artists, activists, philanthropists, community leaders, wise elders, and optimistic youth, all of whom share a deep love and respect for this great and struggling nation. Our work there together challenges the negative and sensationalistic foreign portrayal of the country as we highlight Haiti’s rich and complex culture, creativity, and natural beauty. And of course, our work also aims to balance some of the immense injustice on our planet, where great privilege exists right beside great suffering. So we give back. But really, Haiti always gives more than she receives.

Friends say it’s in my blood to work so passionately in Haiti. My Great, Great, Great Grandfather General Juan José Flores was the founder and first President of Ecuador, who fought alongside Simón Bolívar for the liberation of South America from Spanish rule. He grew up dirt poor himself. He was self-taught, and from a young age he dedicated his life to liberation and social justice. My mother certainly helped steer me back toward that path of our family legacy, giving me a copy of Che Guevara’s Motorcycle Diaries at a very early age.

These pages are a snapshot of Haiti through our lens, as artists determined to inspire and unite our human family to stand firmly together to ensure greater peace and justice for all.

A woman floats off Haiti’s southern coast. Kabic, Jacmel.

Photo by David Belle

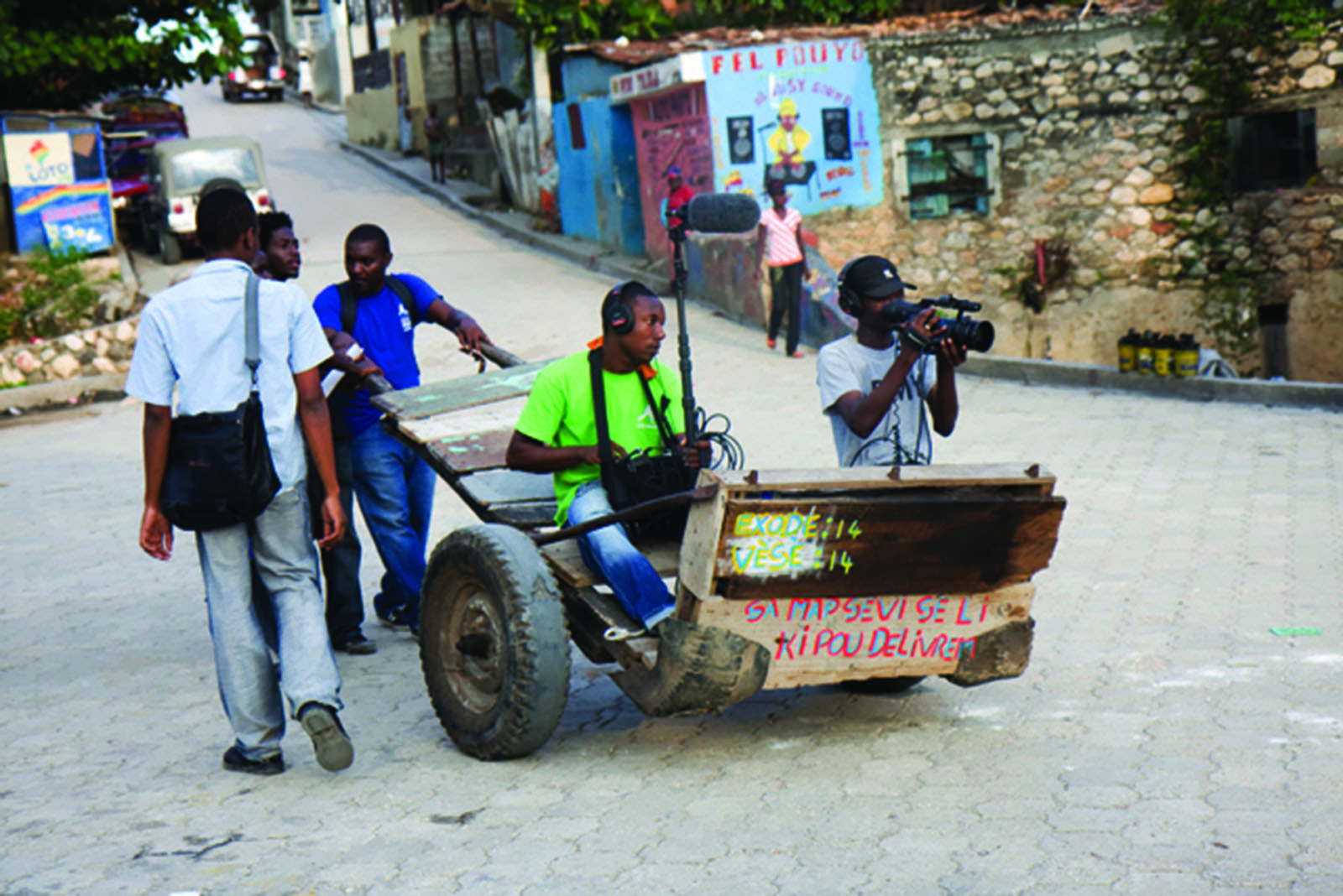

A passing street vendor watches Artists for Peace and Justice members sing with local rappers. Cité Soleil, Port-au-Prince.

Photo by David Belle

Roosvelt Jeudi, blows into a one note horn during photo shoot to create the logo for Audio Institute. Kabic Beach, Jacmel.

Photo by David Belle

Manbo Tiwoz & Hougan Ramon Cesar with Ramon’s daughter in his La Laflé Ginen Vodou Temple. Kafou Pengwen, Jacmel.

Photo by David Belle

Two men in conversation under a street lamp on the eve of presidential elections. Simon Pele, Port-au-Prince.

Photo by David Belle

Chaloska, a character from the annual carnival in the town of Jacmel, representing corrupt figures in the Haitian state. Avenue Barranquilla, Jacmel.

Photo by David Belle

Haiti is a nation of artists, revolutionaries, and Vodouisans. They are the original Black Heroes who defeated Napoleon’s army and declared independence in 1804. No wonder it has been isolated, misrepresented, and misunderstood ever since.

A young merchant sells smoked fish, onions, and hot chili peppers under the light of a kerosene lamp at night. Martissant, Port-au-Prince.

Photo by David Belle

Students at the Academy for Peace and Justice sing “La Dessalinienne”, the Haitian National Anthem before morning class. Tabarre, Port-au-Prince.

Photo by Giles Clarke / Getty Images

Artwork made from recycled rubber tires hung on the side of a residence at the Atis Rezistans cooperative compound. Boulevard Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Port-au-Prince.

Photo by David Belle

Late afternoon on Haiti’s southern coast as the sun comes through the clouds. Route de Marigot, Tessère.

Photo by David Belle

Goatskin drum and mahogany chair. Kabic, Jacmel.

Photo by David Belle

Still from Meryam Joobeur’s short film Artists Institute Portraits. La Vallée-de-Jacmel.

Photo by Marco Saint Juste

Morel Joseph, an artisan in coastal town of Jacmel who makes walking sticks, ash trays, and sculptures out of mahogany. Rue de Commerce, Jacmel.

Photo by David Belle

Anis St. Fleur, a Vodou priest and recording artist with Haitian roots band RAM. Artists Institute, Jacmel.

Photo by David Belle

Tawana Genty and Delzor Obedson, members of Creole hip hop group WA 2 B and senior students at the Academy for Peace and Justice. Tabarre, Port-au-Prince.

Photo by David Belle

Designer Donna Karan and Artist Institute Director Paula Hyppolite lead a class of film students in stretching exercise before discussing a recent photo shoot with Adriana Lima in Haiti. Artists Institute Classroom, Jacmel.

Photo by David Belle

During the start of recess one afternoon at our Academy for Peace and Justice, Paul Haggis and I watched 2,800 kids stream out of the classrooms. He said to me, “I bet there’s a bunch of future leaders in that crowd.”

A young girl watches an Artists for Peace and Justice delegation meet with local leaders. Cité Soleil, Port-au-Prince.

Photo by David Belle

An eighth grade student at the Academy for Peace and Justice, Tabarre, Port-au-Prince.

Photo by Giles Clarke / Getty Images

Students enter the Academy for Peace and Justice gates at the start of a school day. Tabarre, Port-au-Prince.

Photo by Giles Clarke / Getty Images