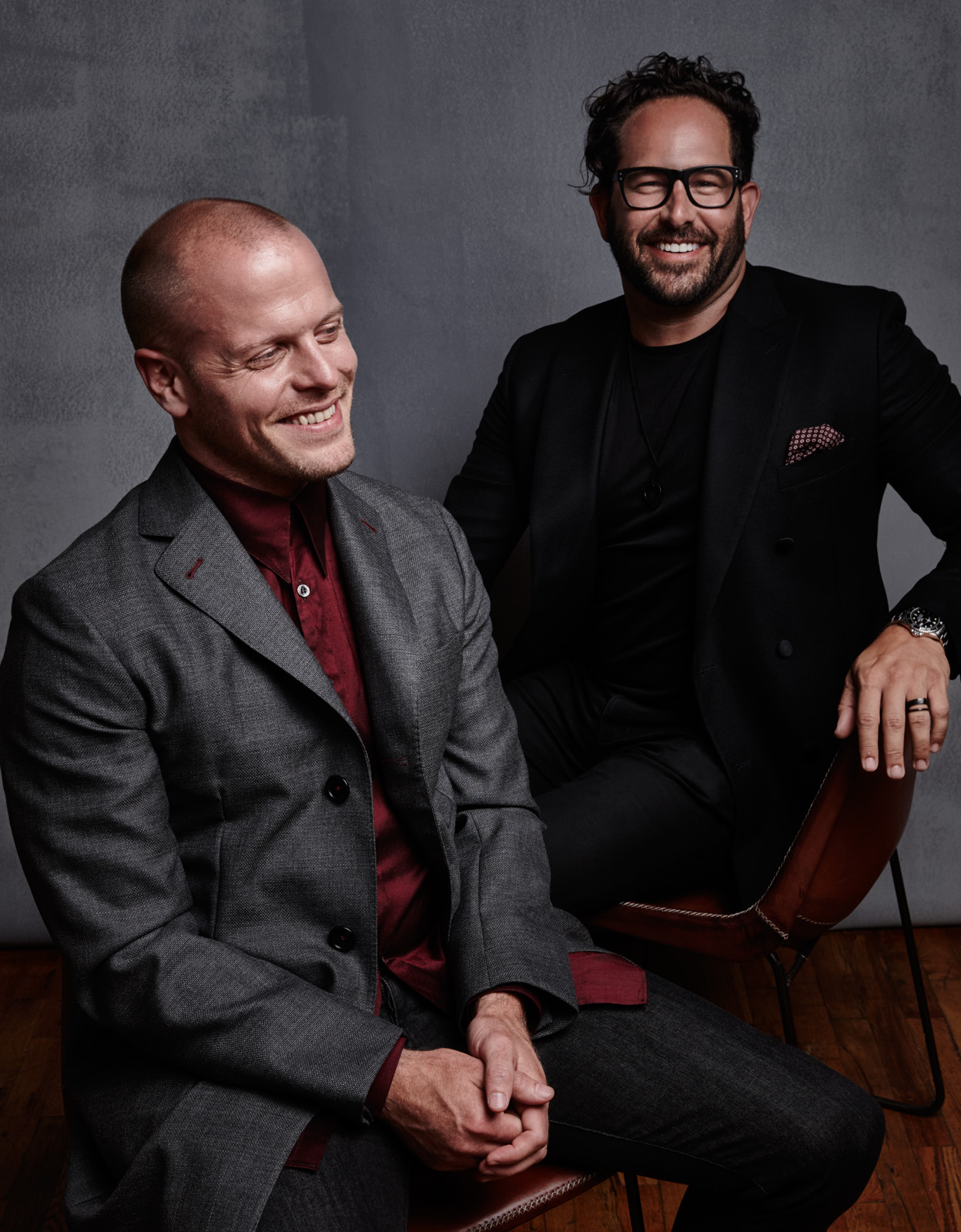

photography by NIGEL PARRY

styling by CYNTHIA ALTORISO

grooming by DYLAN HANSON

studio & backdrops by CHARLES BRODERSON

interview by JASON HARRIS

The author of The 4-Hour Workweek and Tools of Titans believes that enthusiasm and focus are the keys of personal success.

JASON HARRIS: At a cocktail party, how do you describe what you do?

TIM FERRISS: I’m a human guinea pig. I do weird experiments on myself, often resulting in injury, and then write about them. When I’m talking to someone a little older, I mention George Plimpton. In my writing, I tend to give the CliffsNotes on valuable skills – shortcuts for fat loss, investing, time management, etc.

TIM FERRISS:

Coat Stephen F

Shirt courtesy Kevin Creighton

Jeans Paul & Shark

JASON HARRIS:

Jacket, Shirt & Pocket Square Stephen F

Giron Leather Chairs courtesy of ABC Carpet & Home

JH: Did you ever dream what you’d be at this point in your life?

TF: I thought I’d be a teacher for ninth or tenth grade, because that’s a critical inflection point for a lot of kids. It was for me, at least. Or I thought I’d be a comic-book penciler, and I was an illustrator for a couple of years. But life had other plans and here we are.

At this point, I treat my life as a series of two-week experiments or six-month projects. If you have a reliable ten-year plan, you have to sell yourself short in that planning for it to be reliable. So I do as much as I can with a six-month project, and you can’t predict which doors will open.

JH: Your number-one best seller, The 4-Hour Workweek, was rejected by twenty-five publishers…

TF: Twenty-seven.

JH: How did you overcome such rejection?

TF: My plan never was to be a writer. The first title was “Drug Dealing for Fun and Profit,” a tongue-in-cheek name I gave to a lecture I gave twice a year at Princeton for nearly ten years. The notes from that class became the basis for the book. Like a comedian, I’d worked on my material in front of live classes. One of the students said, “I don’t know why you’re teaching a class of fifty. Just write a book and be done with it.” I don’t think he was serious, but that’s how this book idea started. Knowing I could get an emotional response from that target audience gave me the confidence to persist past publisher rejections. I knew the material worked. I had better data.

JH: Most people follow a dream down a path, with milestones of accomplishment.

TF: I try to turn a dream into a goal with a measurable timeline and objectives. Scott Adams, who created “Dilbert,” calls it systems thinking: asking oneself which projects allow you to succeed in the long- term, even if they appear to fail in the short-term. This usually relates to building skills and relationships that persist past a single project. The best option creates more options.

I also focus on the micro to achieve the macro. I focus on small daily ingredients: meditating in the morning, precise physical training, mobility, The Five-Minute Journal, etc.. Those allow me to make good decisions.

Last, in the long-term, the ability to improvise is more important than the ability to plan. People say only the strong survive, but look at nature – only the adaptable survive. We don’t control all of the variables, which is also a reason I study and practice a lot of Stoic philosophy from Seneca, Marcus Aurelius and others. It makes you resilient, or at least, less likely to emotionally overreact.

Shirt Stephen F

JH: Often, accomplishing dreams means overcoming fears.

TF: People don’t achieve goals because fears paralyze them. I do something I call “fear-setting,” in which I write out three columns: the first contains the worst things that could happen if I take the action I’m pondering or putting off; the second column contains things I could do to minimize the likelihood of each of those worst-case scenarios from happening. In the third column, I write how I would get back to where I am now even if each of those things happened. Through that, you crystallize and detail your fears and realize they’re either temporary or reversible.

JH: What are things you want to achieve or experience outside of your career goals?

TF: The ecstasy of the “aha” moment dictates a lot of what I do, both personally and professionally. I want people and projects that will help me find that joy of discovery.

JH: Out of five senses, which are your strongest, and how do they manifest and how do you feed them?

TF: Visual. I have an eerily good visual memory. I routinely creep people out by recounting their exact outfit, seating arrangement, etc. from when we first met. Or maybe the exact design of their business card and shoes from years before. It’s weird, but I’ll take it. It was a huge asset when learning Japanese and Chinese characters, for instance. As for feeding it, I don’t need to do much. I soak in my surroundings every day.

JH: You have many, MANY interests; why does something or someone become interesting to you?

TF: Generally, if someone else is excited about it and infects me with that enthusiasm. I can get excited about the most “boring” subjects imaginable if someone else gets hyped up about it and can explain what everyone else is missing.

JH: What is lucid dreaming?

TF: It implies being conscious of the fact that you’re dreaming while you’re dreaming. On the rare

occasion that this happens, people usually get excited

and wake up. But you can develop the ability to induce that state. How did we prove lucid dreaming

exists? Eye movements in a dream correspond to physiological eye movements, like REM sleep. Test subjects would agree on a sequence to indicate they were conscious (example: right-right-left-right-

left-left), and then would be attached to devices that measure brain waves, correlating the fact that they’re absolutely asleep. There are some cool studies out of Stanford, I believe.

JH: That’s amazing.

TF: I used it when I competed in wrestling long ago. I would “train” with Olympic champion John Smith – I’ve never met him, but I would watch his videos, become conscious that I was dreaming, and envision training with him, like the dojo in The Matrix. That was the first and only year I was an All-American in high school.

To train this ability to induce lucidity, one does reality checks throughout the day to get better at distinguishing between waking and dream states. In a dream state, when you look at text, then look away and look back, the text will always change, as your brain is recreating the environment. Or if you look at the orientation of bricks on the floor, look away and look back, they might flip ninety degrees. It’s like spinning the top in Inception. You get better at this type of discernment by practicing and asking yourself, “Am I dreaming or awake?” Much like meditation, it brings you into a present state of awareness repeatedly, so you end up more effectively relaxed, even in your normal waking state.

JH: What about visualization versus lucid dreaming?

TF: Visualization in a waking state rehearses something you want to accomplish. Studies look at the ability to improve strength through visualization – you envision in real time the imagery of weightlifting exercises you’d do at the gym, which means that if the workout would take ten minutes, you visualize the entire workout for ten minutes. There are some amazing gains for the visualization cohort. But in this instance, I prefer to simply do the workout!

JH: Is that to train or to trick your mind and body to achieve the goal?

TF: Both. People in the studies experienced strength gains without weights, so there is some trippy stuff out there. We’re barely scratching the surface of the hardware and software between our ears. And of course that ties into the fascinating, underexplored subject of hallucinogens and micro-dosing.

JH: Does that open you up to visualization?

TF: It can. Micro-dosing would be considered non-hallucinogenic, so it’s often sub-perceptual, but I notice odd effects. Nobel Prize-winning breakthroughs in chemistry and the hard sciences, including genetics, can be traced back to judicious use of hallucinogens, in most cases LSD. But some of the same effects – anxiety-reduction and creativity improvements – can be elicited with micro-doses. What’s appealing is that you can function normally with these tiny amounts. I’ve experimented with micro-dosing twice weekly of ibogaine, and it’s been extremely fruitful and fascinating. Seems to definitely open up channels of perception. That said, most of this is incredibly illegal with severe penalties, so be aware of the risks.

JH: What in particular would you take micro-doses for?

TF: Anti-anxiety, anti-depression and creativity.

JH: And you can function in day-to-day activities?

TF: I could be micro-dosing right now and you wouldn’t notice. I might just have an enriched vocabulary.

JH: How did you transition from writing to podcasting?

TF: I was a guest on a podcast, and it was so refreshing to be myself in a long-form interview – to curse and embrace my quirks and weirdness. Not to knock morning TV, but some of my books are five hundred pages, so a fifteen-second sound bite doesn’t offer much.

I realized my favorite part of writing is the research, interviewing experts, the testing. The podcast represented the opportunity to do my favorite part of writing, without the writing. But more important, I could get better at asking questions, fix my verbal tics – the ums, ahs, “likes”– and interact with people I otherwise couldn’t or wouldn’t. Even if the podcast was a commercial failure, the tools I developed would help me in other areas. Because speech and writing are crystallized thought, how you speak is how you think. That’s why I rarely edit my interviews. It’s one take, which forces me to concentrate and not get sloppy.

JH: Are you done with writing?

TF: I thought I was. The podcasts have been so much fun, and from financial and creative standpoints are by far the highest ROI activity I’ve done in terms of hours invested. I’m now reinvigorated to write and just published Tools of Titans, a book of the best tricks, habits and routines from podcast guests who impacted me. For the first time, I really enjoyed writing a book. I think it’s my best work.

JH: On the human guinea-pig path, you studied maximizing performance. How much sleep keeps you at the top of your game?

TF: When I can do monophasic sleep, which is what most people are accustomed to – one block – I like eight to ten hours. If you feel you need to

cut back on sleep to get things done, your priorities are out of whack. If you don’t have time, you don’t have priorities. If I use polyphasic sleep – breaking sleep into sections throughout the day – I can go as low as two hours a day. Matt Mullenweg, the CEO of Automattic, used polyphasic sleep for a year to write a lot of the code base for WordPress; it was his most productive coding year in his life. I asked why he stopped, and he said, “Got a girlfriend!” Intimate relationships don’t work very well when you have to take a nap every two-and-a-half hours.

Doing monophasic sleep, I would regularly take a caffeine nap around two o’clock. I would have tea or espresso and immediately lie down for twenty minutes. The key for an effective nap is not having sleep as an objective; think of it as simply resting your eyes and removing sensory inputs, and you’re more likely to fall asleep.

Back to a normal night’s sleep, though – I had terrible insomnia for a long time. The late Professor Seth Roberts would mix a cocktail of two tablespoons of apple cider vinegar and a tablespoon of raw honey into hot water. It’s like a tranquilizer dart; friends who’ve had insomnia for fifteen years say it’s helped more than prescription medication. Then again, I’m not a doctor and don’t play one on the Internet, so take it with a grain of salt.

JH: For those trying to accomplish their dreams, what’s a good structure for the day?

TF: It’s worth looking at weekly routines. Some of the most effective people I’ve run into, like Jack Dorsey, will batch activities into specific days instead of fragmenting the day. So Monday might be HR and hiring, and the next day is dedicated creative work with all distractions blocked out. Otherwise, you suffer from task switching each day. If you’re a coder or writer, for instance, you think you have time for a five-minute phone call, but it’ll take twenty minutes to get back to what you were doing. Three five-minute phone calls waste an hour of creative work. Batching tasks is critical.

Broadly speaking, if you win the morning you win the day – your recipe should involve as few decisions as possible. Figuring out what to have for breakfast is a huge waste of cognitive resources. You should be on autopilot for the first hour or two. For me that involves waking up, twenty minutes of meditation, setting up pu-erh and turmeric tea, feeding the dog, having a can of Wild Planet sardines, and using something called the five-minute journal to set priorities and gratitude for the day. Then an hour of writing. And that’s before I turn my phone off airplane mode – no incoming texts, no e-mail. If I do that, the day is won.

JH: When it comes to fashion, successful people like Steve Jobs have one outfit and don’t deviate from it, reducing their minor decisions. What is your sense of style?

TF: I am notorious for not having fantastic fashion sense – at least my ex-girlfriends say that. I do either end of the spectrum and nothing in between for a lot of things. With fashion it’s either pure comfort and pjs with slip-ons, or a t-shirt and hoodie, or it’s a really nice, tailored suit. I don’t have to think about matching, except for perhaps shoes and belt. In San Francisco everyone is a slob. You can improve your fashion by choosing a place to live where the reference point is really low.

I do the same a lot in business. My speaking engagements are free, or full retail and as expensive as possible. I used to negotiate the muddy water in the middle, and it chewed up hundreds of unnecessary hours. Now it’s easy and binary.

If you’re having trouble making decisions, perhaps you just need to engineer your life so that you have fewer options.

JH: We are living in the age of “brands” and “brand building.” Do you have a description of what your brand is?

TF: Honestly, I don’t ever think about my “brand.” I get asked about how to build a “personal brand” all the time, and my answer is simple: It’s a distraction. Focus on putting out the best product you possibly can, focus on building it for your 1,000 most die-hard fans (who are your best marketing force), and the rest all takes care of itself.