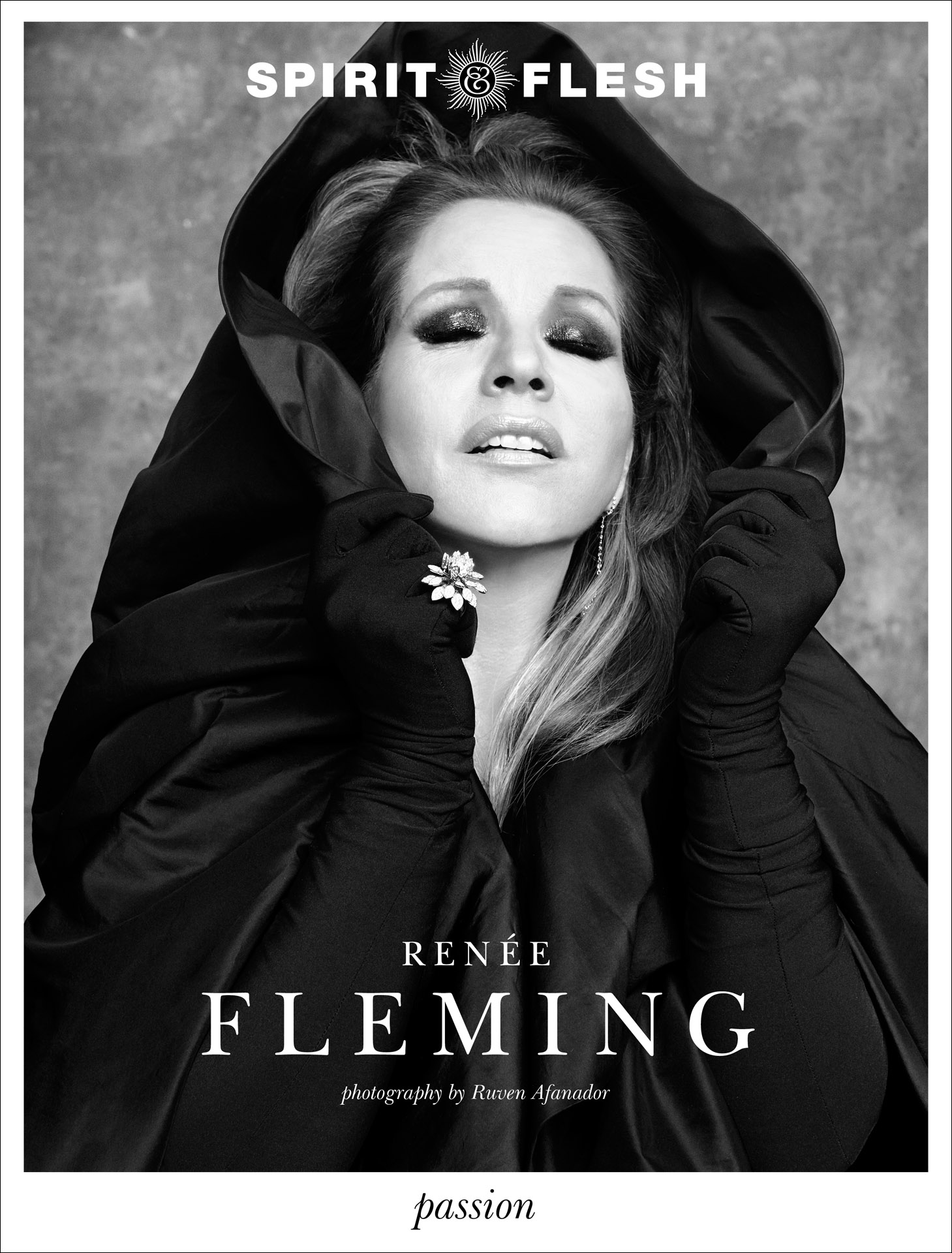

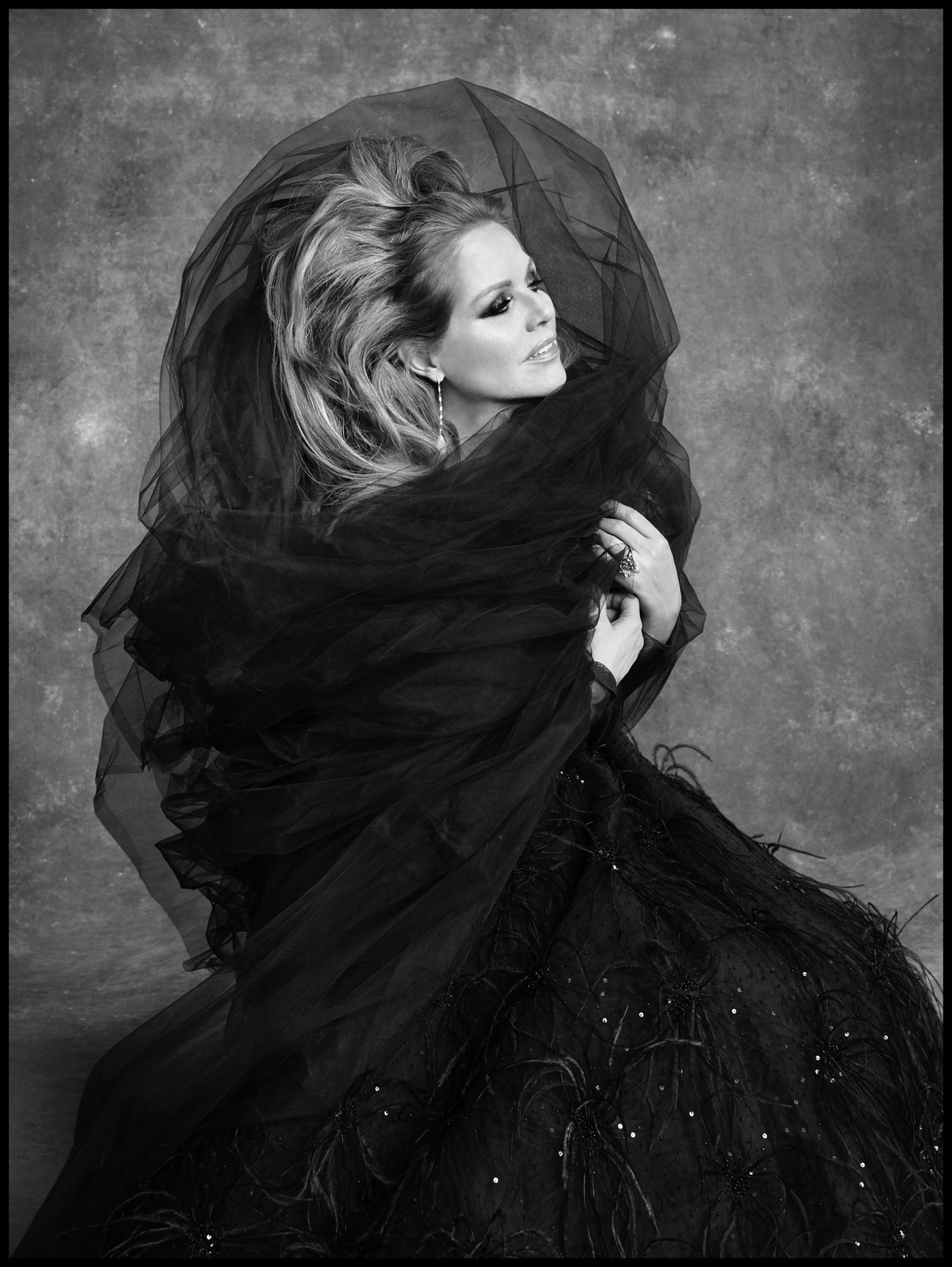

Renée Fleming speaks to Andrew Basile about her life in and beyond opera.

ANDREW BASILE: What are you most passionate about?

RENÉE FLEMING: This will come as no surprise: I’m passionate about singing, but I don’t mean just classical or opera. I love great vocalism in virtually every style, whether it’s gospel, jazz, bluegrass or world music. The voice is our most primal expression – direct and unique to each individual. It also says a lot about our national culture and identity.

Order your PASSION issue here.

AB: You have what has been described as a “classically beautiful voice.” Can you describe your sound, how it differs from others?

RF: I’m the last person to be able to, since I hear it from inside. It’s crucial to have a distinctive sound; a recorded voice should be immediately identifiable. While beauty is in the ear of the beholder, it’s recognizable because of purity, warmth, expressivity and a mysterious ability to touch the heart. The instrument is the singer’s body. So my sound is the particular result of studying a technique that is hundreds of years old and applying that to my own physiology.

AB: Is there one person that you would like to sing to, personally and directly?

RF: Because I’m always preparing music for work, I don’t sing at home for pleasure as much as I’d like. My husband jokes that it took me three years to sing “Happy Birthday” to him.

AB: You’ve mastered an array of music of contrasting styles from jazz to bel canto, from lieder to indie rock. What else would you like to explore?

RF: I love the Appalachian sound of what’s often referred to as “roots” music. It’s spare, with simple instrumentation but enormous emotional power.

AB: You are waiting in the wings for the curtain to rise and are the first to sing – how do you feel?

RF: Pensive, absolutely focused – this is where the preparation has led. Once I step onstage, ideally all that preparation and technique becomes second nature and I can let go in performance.

AB: You have two daughters; would you like them to follow in your footsteps and what would you like them to learn from your experience as a public figure?

RF: I absolutely want them to follow their own paths; they’re smart, talented young women. I hope my experience has taught them to live on their own terms and find a balance. I was lucky to be able to take them on travels when they were small, so I also hope my life has helped them be “global citizens” by introducing them to places and people they otherwise wouldn’t have encountered.

AB: You are asked to make a movie of an opera ofyour choosing. What do you choose?

RF: Operas that succeed as films are those with complex psychology. For something I might sing, I’d look to Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier, but Janácek’s Jenúfa would make a gripping film – the psychology is modern. It’s extremely dramatic and intense but quite believable.

AB: You seem to be the “anti-diva.” What keeps you grounded within your demanding schedule of performances and personal appearances?

I like the concept of the diva onstage, in the old sense of the word – creating an experience or a character within an opera, that reaches for something divine. But I’ve never (I hope) been able to muster the diva persona offstage.

RF: I think I was born that way. My family has also been a constant focus. When you raise children and give and receive emotional support within a larger structure, it’s hard to indulge in diva behavior. Children don’t tolerate it because they’re at the center. Mothers usually don’t have the prima donna spot at home. I like the concept of the diva onstage, in the old sense of the word – creating an experience or character reaching for something divine. But I’ve never (I hope) been able to muster the diva persona offstage. I got to let out my inner diva in Living on Love, which I recently performed on Broadway, and it was so much fun. I played a grand, narcissistic prima donna of the old school.

AB: What is an exciting night out to you? What do you enjoy outside of your work?

RF: I’m a culture fanatic. If I’m not performing you’ll find me in a museum, at the theater, attending a concert or in a jazz club. I would love more time to read poetry, and I’m just starting to discover some great television.

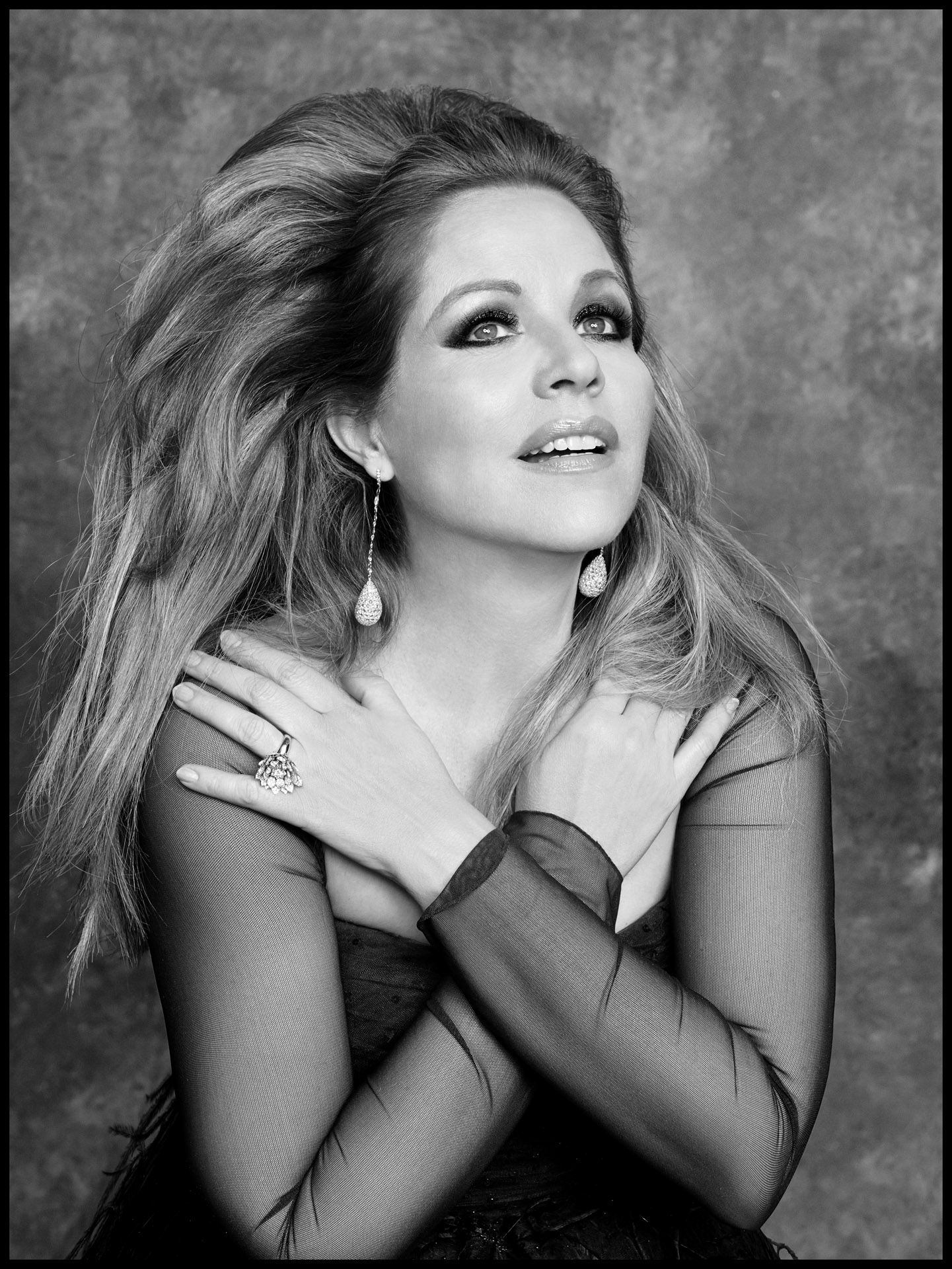

AB: You are stylish and current off-stage, and radiant on. Describe your connection to fashion and its importance to shaping your image.

RF: There was a line in the play Living on Love, where my character said, “opera is better than life,” and I think that’s true. Audiences have high expectations of glamor for opera singers; people want to be swept away by the beauty. I love it because it gives me license to wear and showcase the work and vision of great designers.

AB: How do you choose a role? And which roles do you feel best suit your voice and personality?

RF: I’ve sung more than fifty operas so there aren’t many new roles to consider. I felt the strongest connection to the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier; she’s complex, sympathetic and strong. I love the women in the operas of Richard Strauss who had a unique gift for writing for sopranos, perhaps because he was married to one. Also, Tatyana in Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin – I love her initial bookish timidity and her strength.

AB: What’s next for Renée Fleming? Where do you plan to take your talent?

RF: The exciting territory for me now is outside opera. As I sing more concerts and recitals, I enjoy creating characters or narratives through the music I program. Another role I find rewarding is working as creative consultant at Lyric Opera of Chicago; I’m confronting the challenges of keeping this art form relevant and developing ways to engage new audiences.

AB: With which singer from the past would you most want to sing?

RF: I could never choose. Think of all of the legendary voices before the advent of recording! The digital age is a thrilling time to be a musician, though. Instead of hours scrambling in a music library, musicians today can hear almost anything immediately on the computer. The distribution of music and the way it is experienced have changed radically over the past couple of decades. It’s putting enormous pressure on classical artists to adapt. I find that challenge exciting.

AB: You have worked hard to achieve your goals; what do you find most personally gratifying?

RF: In a time of almost universal amplification and electronic manipulation of singing, I admit to some pride in being part of a tradition of vocalism that places Olympic demands on singers. The virtuosity of what we do is rare and powerful. I love and admire all kinds of singing, but to be able to sing unamplified over a seventy-piece orchestra to the back of the balcony – that takes intense training and commitment. That’s gratifying not only in performance but in preparation: There’s a vast body of knowledge to acquire – singing in multiple languages with refined stylistic differencesbetween Russian, French, Italian and German music – and hundreds of years of repertoire. Talent is only ten percent, given what one has to learn. At its best, the power and beauty of this tradition moves people to tears.

AB: To be able to sing is extremely personal as you are the instrument. It’s also transforming to a listener as your voice has lifted me and others through some difficult moments. If you could heal some of the wounds of the world through the power of song what song would you sing?

RF: A month after 9/11 I was asked to sing at Ground Zero at the memorial service for the families. It was daunting to sing for people who had suffered so recently and so deeply. The song was “Amazing Grace,” one of those indelible anthems that elicit a universal response. You find songs like this in almost every musical tradition. Since the very first song was sung, people have known that music has the power to heal and unify.