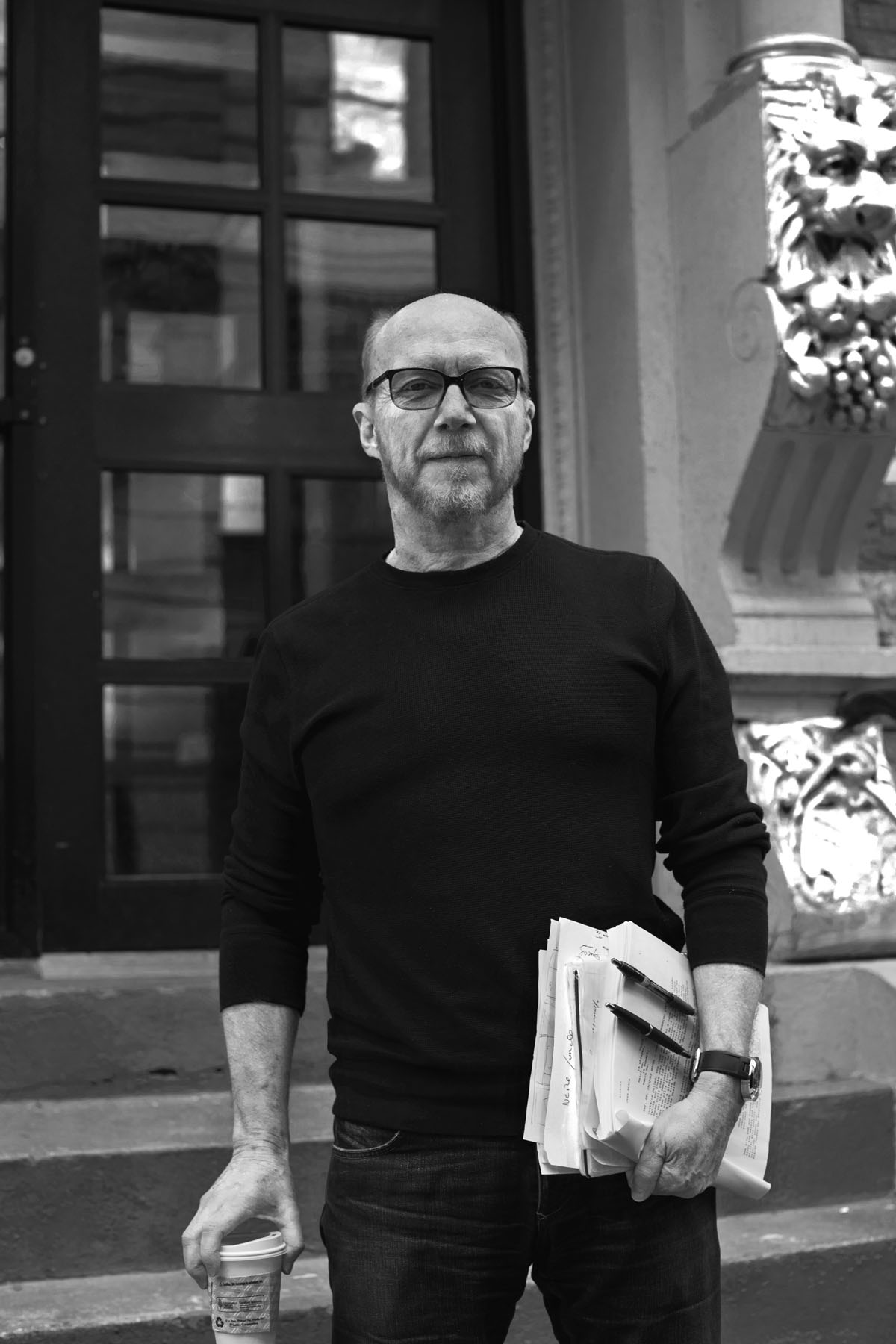

photography by GUZMAN

interview by YELENA DEYNEKO

styling by BASIA ZAMORSKA

grooming by OLGA POSTOLACHI

lighting equipment SCHEIMPFLUG

location HÄSTENS BEDS, INC.

WEST 18 & SOHO SHOWROOMS, NYC

You may also like film-interview with Paul Haggis, to view click HERE.

Paul Haggis Talks About Privilege, Responsibility, and Love.

Yelena Deyneko: What essential skills did you learn from your early career as a photographer?

Paul Huggis: It was a great training, as I learned about light and optics. Any director needs to understand how a particular lens affects a character and the scene. You trust your director of photography to light the scene, and sometimes choose a lens – but they need to understand what you want to express emotionally through those choices. For example, on Show Me a Hero I had a great DP, Andrij Parekh, a real artist. We had a scene in a courtroom where eight characters were in a tight huddle, under a lot of pressure. After shooting the master from above, we needed to move in for closer shots. The DP rightly suggested that the best way to accomplish that was with a long lens, from outside them – but I wanted the viewer to feel the pressure the characters were under, so we jammed a very short lens right between them. It was difficult to shoot, but it had the effect I wanted – you feel like you’re right there and under pressure with them.

YD: Why did you become a filmmaker?

PH: The photographer captures a moment, but the story he or she tells is just of that moment. I wanted to tell bigger stories. And I’ve always been concerned with our impact on society and responsibility to others. Sometimes those two things fit together nicely and sometimes they don’t.

Pajamas Hästens

Bed Hästens Luxuria

Equipment Scheimpflug

YD: How did Crash develop?

PH: While I loved living in LA, I was often disturbed by what was going on just out of our sight. I grew up in a working-class family in Canada, and my parents fought to get into the middle class and succeeded – they did very well. But I have never been comfortable with privilege. As much as I really like the perks, it still makes me uneasy at times. In LA, if you care to look, it is easy to see the imbalance in the system – the subtle and not-so-subtle racism and intolerance, and people’s attempt to deny its existence – especially people of privilege. We all want to think we are good people, that we wouldn’t tolerate social injustice around us – but we do, by closing our eyes to it. I was as guilty as anyone else – that’s what I wanted to write about. How we isolate ourselves, and how we suffer from that isolation. So we wrote the script, Bobby Moresco and I, and our producer Mark Harris and my agent Larry Becsey ran around for years trying to get it financed – which was challenging because of the subject matter, and because I had no track record as a director.

YD: Because you have an audience, is it your duty to raise issues?

PH: Yes, but it’s also really important not to take yourself too seriously. We also have to entertain and, at times, lift people up. Charlie Chaplin was very political, but believed his biggest responsibility was to make an audience feel; to make them laugh and cry. Some stories I tell are political, some social. But often I am at my best when I hide any message I have deep inside the story, as with Casino Royale. At the moment, I’m writing what could be called a “young adult” movie – the question I want to ask, whatever message I want to convey, is there – but you have to dig to uncover it. You have to respect your audience, trust that they are curious, and will look deeper than the obvious.

YD: Isn’t it a game of art and commerce?

PH: Always, because you must get others to finance your idea, which they do based on how successful they think the project will be and on the success of your last films. If your films are challenging, if you are saying things that the audience doesn’t necessarily want to hear at that moment – like, for example, with my film In The Valley of Elah, it can make getting financing for your next film harder. Same with a personal film like Third Person, which was my homage to the New Wave filmmakers of the 60s. I knew both those films weren’t going to be big box office or even critical successes – but I am very proud of both of them. Critics used to understand film and love new ideas; now more often they’re guardians of the status quo. They know how a movie “should” be made – and if you make it outside their rules they can react viciously. But if you look back, this has always been the case. We forget that many of the films we now hold as classics were panned by the critics in their day. On some of my films, I’ve found it easier to get financing in Europe or elsewhere. On my more conventional films, it is easy to get financing here.

Watch Bovet 1822

Tuxedo & Shirt Brioni

Tie Dolce & Gabbana

Equipment Scheimpflug

YD: With collaborators, how do you know when to stand your ground?

PH: It’s a gut reaction. When I first started directing, my people skills were very poor, and I found it hard to prioritize and manage time. I would shoot too long, push the crew too hard. I have to admit I am still pretty demanding, but I hope that now my crew feels that we are all struggling together. I can’t always choose my team – often people I love who I’ve worked with before are busy – but I have been fortunate to work with some many amazing talents. You have well-deserved bragging rights. Everybody likes to be told they’re good at what they do, but you’re only as good as the project you’re working on at the moment. I have always thought that I would have to make ten films that I considered “great” before I considered myself a success. I’ve only directed four films, so I have a long way to go.

YD: Are you proud of all of them?

PH: Very proud, yet I would change everything. I’ve made some stupid mistakes, but they led me to where I am. We often live in fear of mistakes when we should be celebrating them; they lead to realizations and ultimately make whatever you’re doing… human.

YD: Do you have a big ego?

PH: Pride is probably my biggest problem. I struggle with it all the time. I mean, we all have moments when we don’t think we’re being treated fairly – we think people are demanding too much and returning too little. In my case, when I feel that, it’s almost always not true – it’s only my ego. I remember asking Clint Eastwood’s wife, “How is he so down-to-earth?” and she replied, “He works on it every day.” Whenever I feel full of myself, when I’m not just truly grateful, it’s embarrassing. Hopefully I keep learning.

YD: What stimulates creativity?

PH: Above all, curiosity about our world. And then a story hits you. It can come from conversations, research, a song – you never know where. But starting to smell a good story is like falling in love.

YD: Are you in that stage until the movie is done?

PH: Yeah, my last one was five years. And then you’re finished with the film, it breaks your heart, like losing a lover. You think you’ll never fall in love again, never find another project, so you search for the next one even before you finish the last. It’s addictive, that high you get from something that troubles as much as it excites; you know it’s going to be a terrible, wonderful ride. Sometimes I work sixteen hours a day and am exhausted, but happy.

YD: What are you working on now?

PH: I have a few things, but I don’t like to talk about them. Too many people in our business talk a good game and nothing ever comes of it. Ask me again when I actually start shooting one of them.

YD: Do you ever become your characters?

PH: Some friends read my scripts and say, “It’s just you, Paul.” Yeah, there is always a piece of me in my characters – often not the nice bits.

YD: Is it difficult to tell the truth about yourself?

PH: Some questions are disturbing, and I hate the answers: “What would I actually do in this situation?” Or, “I say I would do anything for the woman I love, but would I really?” We all think we know who we are – but we never know until we are tested. That’s my job, to test my characters and see what’s revealed.

Watch Bovet 1822

Tuxedo & Shirt Brioni

Tie Dolce & Gabbana

Shoes Moreschi

Socks Happy Socks

Bed Hästens Vividus

YD: What do you hope people learn from your movies?

PH: Artists and filmmakers and storytellers shouldn’t answer those questions, because it takes away from the art. We’ve been trained that movies should give us answers, and that they should be in capital letters, underlined and in bold so we don’t miss them. That’s a form of entertainment that the public and even critics have come to like, but it does a disservice to leave you without questions.

YD: What can’t you live without?

PH: If I don’t get a good night’s sleep, I can’t create. I used to worry so much about directing, and I’d stay up so late making my diagrams. The next morning I’d be exhausted. You’d get to the set and six problems would be presented to you before you even step out of the car. If you are tired you can’t think as fast as you need to, can’t solve those problems – and you have a cast and crew of a hundred people there who need those answers and fast. So, long ago, I decided that the best way I could prepare was by being well-rested and alert. Then I can deal with anything. When young directors ask for advice, I say, “Get a good night’s sleep.” But then I often wake up and write my best ideas at three in the morning; that’s how I came up with the idea for Crash. And even now, when I’m stuck, I go to sleep with a question: “What should this character do?” Sometimes you press and press and can’t find a solution – but go to sleep and it comes from your subconscious.

YD: Are you excited about the future?

PH: Very excited, and terrified. We have amazing new technology, but do we have the wisdom to use it – to truly solve our problems, rather than just distract ourselves from them? One of my greatest pleasures is the work we do for the children of Haiti with Artists for Peace and Justice. As you know, Haiti is by far the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Our organization has raised over $25 million to help Haitians build new institutions. With the help of our wonderful sponsors like Bovet 1822, Vhernier, Brioni – and now Hästens – we are able to cover all our operational costs, so that 100% of the money we raise from the public goes right to the work on the ground, where it is so desperately needed.

YD: How did you start it?

PH: I read about this man, Rick Frechette, doing incredible things in the poorest area there. Frankly, he sounded too good to be true, so I went to find him. I was wrong – he was doing so much more than I could possibly comprehend – and he was doing it all with almost no resources. It profoundly affected me, and I knew I needed to help. I saw what things matter.

YD: Such as?

PH: You don’t have to solve poverty, but everyone deserves to be treated with dignity. I can see it in the eyes of women and children in slums. They have such fierce pride. They do not want charity, they want a chance. That is all we are trying to give them; a fair shot at life, and that starts with a decent education. Whether we live in a New York penthouse or in a shack in the slums of Cité Soleil, diginity is something no one should be asked to live without.

Watch Bovet 1822

Sweater Brioni

Pants Dolce & Gabbana

You may also like film-interview with Paul Haggis, to view click HERE.