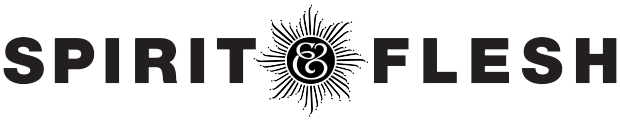

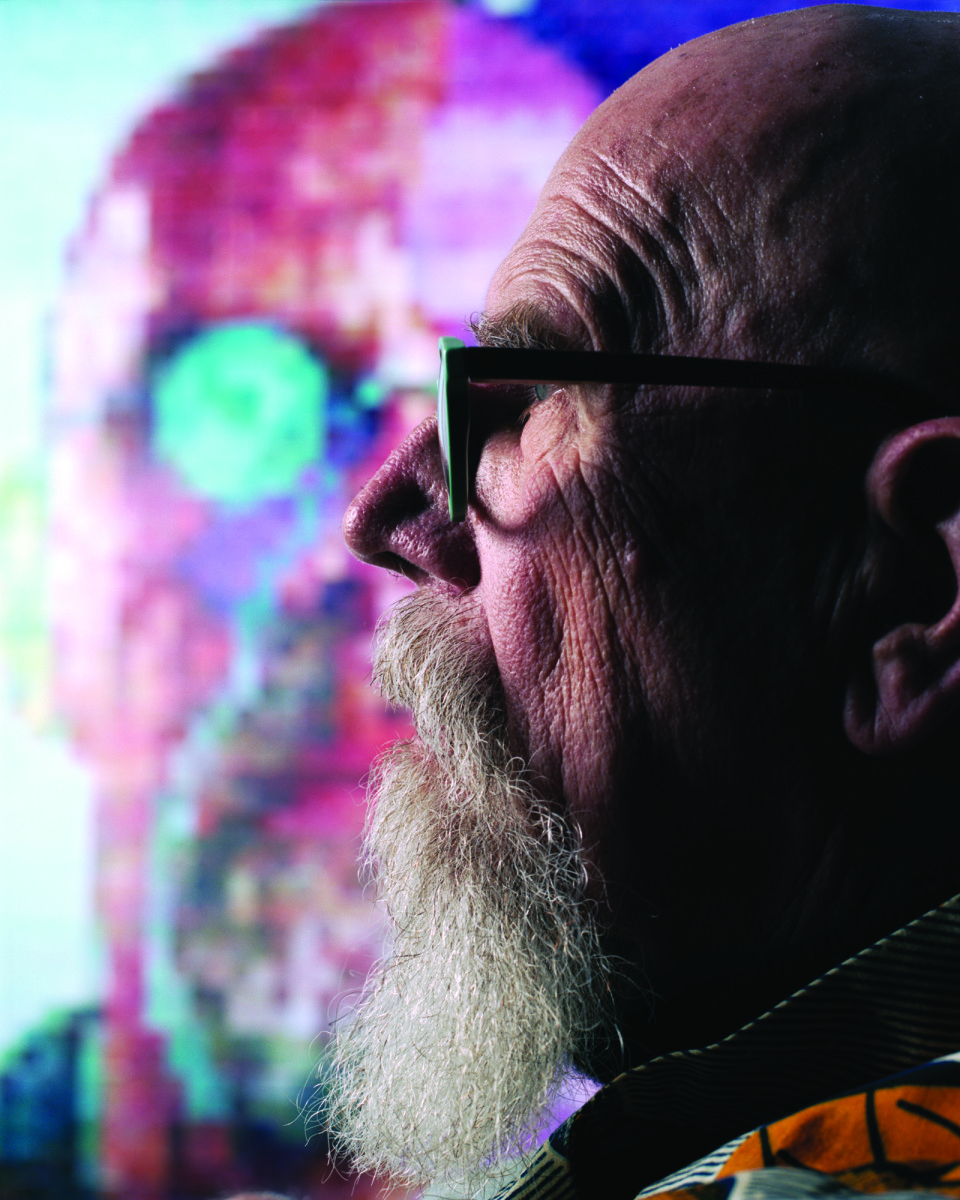

My brother Antonello and I felt apprehensive to photograph CHUCK CLOSE, but once we got underway at Close’s Noho studio, the great portrait artist exceeded his reputation of kindness. Almost immediately he entrusted us with the direction of the shoot – the ultimate show of respect for an artist. A wonderful conversation about some truly important things sparked an unforgettable collaboration.

What compelled us most was Close’s insatiable desire to know life and how to live, one of many great qualities that place him among the most prodigious living artists.

ROBERTO PATELLA: When did you realize that art would become your life?

CHUCK CLOSE: I knew I wanted to be an artist at age five. My father made me an easel for my fifth Christmas. By age eight, my father had enrolled me in private art instruction in Tacoma, Washington, where I actually drew and painted from live nude models. I’ve been trying to get women to take their clothes off ever since.

RP: Talk about starting them off young! Can you recall any other figures who encouraged you?

CC: Well, my father died when I was 11, but I had some mentors. Even in a poor, white-trash mill town [Monroe, WA] we had art and music. It was a guaranteed right; every school in America had to have art and music several days a week. If I hadn’t had that, I don’t know what I would have done. Dropped out of school probably. I was so learning-disabled and face blind [Close suffers from prosopagnosia, a condition marked by an inability to recognize faces], I couldn’t memorize a thing. I never learned to add or subtract, multiply or divide.

RP: You were a teacher at University of Massachusetts for awhile. Did your students inspire you?

I’ve always said inspiration is for amateurs.

CC: I’m not a big believer in inspiration; I’ve always said inspiration is for amateurs. The rest of us just show up and do the work. To sit around and just wait to be struck by a bolt of lightning – it may never happen. Everything grows by the work itself and doors open because of that. You know, the public has this belief in inspiration, that if something happens it’s because somebody turned on a light bulb. I just never found that to be credible.

RP: So how has interacting with other artists in New York affected your work?

CC: It’s important to know what they’re doing but you don’t want to make anything that looks like theirs. You’re driven in your own personal direction and that’s antithetical to the idea of someone influencing you. Although it is an influence, it’s an influence in the sense of, “Oh, shit, now I can’t do that.”

RP: So it’s a process of elimination?

CC: You can’t afford not to know. Nobody gives you a free pass because you’re ignorant.

RP: Is that what encouraged you to move to New York?

CC: I always liked to live on the water, and Western Massachusetts is land-locked. Anyhow, I hated it there. It’s much more important to be in an arts center like New York where other people agree that what you are doing is important. If you are in the Midwest somewhere where no one else is doing much, you don’t have a community. You are not making stuff for others to see and have dialogue with other artists. It’s very hard to be an artist. You’ll be an outsider artist, perhaps. The sophistication of your work depends on exposure. Just like how I wanted to get out of Seattle. There was much interest in Asian and Native American Eskimo art there but they weren’t interested in what I was interested in. I wanted to get to New York.

RP: Would you elaborate on face blindness and what that was like for you as a child?

CC: It was horrible. At the end of each school year I couldn’t distinguish between those who were in my class versus others, let alone tell what their names were. It was a real problem.

RP: Has this shaped your art?

CC: Everything that I am and have become is directly related to my disabilities. It’s my life.